Let's explore the Kalamkari art form!

Introduction

Etymology: The word 'Kalamkari' evolved under the Sultanate's rule in Golconda. 'Kalam' or 'Qualam' means pen and 'Kari' translates to work, so it literally translates to pen-work. Another justification for the naming of Kalamkari is that the artisans were called Kalamkars; hence the work they did came to be known as Kalamkari. The Kalamkari scrolls, referred to as 'pattchitra' by some, were also known by other names such as 'Chintz' by the British, 'Pintadoe' by the Portuguese, and simply 'Kalamkari' by the Mughals.

Origin: Kalamkari paintings were developed in the 17th century in Golconda region of Masulipatnam. The region was then under Nizam's rule, which had Persian influence. The temple-influenced paintings of Kalamkari originated in Srikalahasti, which is a temple town in the Chitoor District of Andhra Pradesh. The 'Karrupur' style of Kalamkari was beginning to develop in the Thanjavur region, which involved adding golden brocade work to woven textiles.

Location: The art style of Kalamkari is spread throughout the states and cities of South India. Kalamkari thrived in the regions of Golconda, Srikalahasti, and Thanjavur.

Community: The temple-style kalamkaris from Srikalahasti are made by a community called 'Balojas', who are a bangle-making community, whereas the Masulipatnam style of kalamkari was influenced by Persian designs as the artisans travelled with the Nizams and settled in Masulipatnam. The artisan community who made these designs were called 'Naqqash'.

Relevance: The importance of the Kalamkari paintings arises from the practical purpose they served. Kalamkari textiles were a portable substitute for the immobile religious temple architecture and statues.

History

Historical Background: The Naqqash community of Masulipatnam introduced and implemented Persian motifs and designs to the kalamkari art style, whereas the Balojas community of Srikalahasti exclusively focused on painting the Hindu deities and illustrating Hindu epics which were considered to be temple art style. And the Karrupur style brought in the influence of the gold leaf technique of Tanjore paintings.

Culture and Societies: Kalamkari scrolls are similar to temple murals in that they depict epic and mythological stories from religious texts, providing an illustration and explanation of these narratives and conveying religious messages to viewers. The 'Bhakti cult' has had a positive impact on the artisans as it has led to the documentation of these stories on temple walls in the form of illustrations. The illustrated medium served as an educational tool without the need for a narrator, unlike other forms of storytelling such as dramas, songs, and dances. Scroll narratives are a combination of multiple strategies for the transmission and interpretation of religious stories. They are highly regarded for their visual representation and are accessible to both the elite and commoners. The patrons and benefactors of this art form have included emperors, feudal kings, local lords, chieftains, businessmen, and merchants from nearby and far-off areas.

Religious Significance: Earlier wandering minstrels would carry these tapestries with them as they would spread the name of God by going from one place to another. These tapestries would have illustrated paintings of mythological figures, which aided them in spreading the art of the 'chitrakatha' tradition of folk and tribal communities. The kalamkari paintings created by the Balojas community are still in demand as they are the only surviving community to make these religious tapestries.

Understanding the art

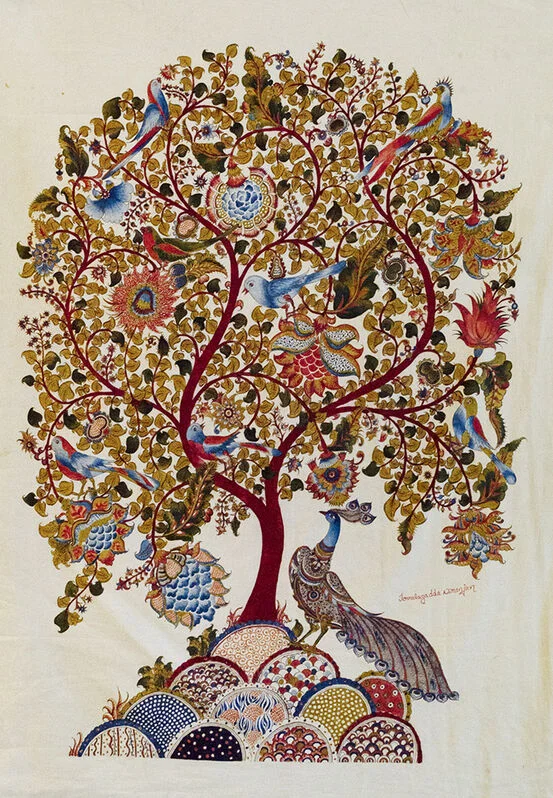

Central Motifs and their Significance: In the Masulipatnam Kalamkaris motifs such as trees, creepers, flowers, and leaves were painted; whereas the Srikalahasti Kalamkari paintings depicted the Hindu Puranas and epics such as the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, and other mythological scenes and stories. Singular deities such as Krishna, Brahma, Ganesha, Durga, Kiratavinyaarjuna, Lakshmi, Rama, Shiva, and Parvathi were also painted in the temple-style paintings. The tree of life is a popular motif in kalamkari paintings.

Mediums Used: The Srikalahasti artisans used natural resources such as bark, flower, and roots for extracting natural dyes. Besides, elements like madder root, pomegranate seed, mango bark, and myrobalan fruit were used to make pigments like red, yellow, and black, respectively.

Style: The Masulipatnam school of Kalamkari paintings incorporated Persian-inspired motifs, which were intricate. They used traditional woodblocks to print the patterns and motifs. The colour scheme was bright with the use of primary colours. The Srikalahasti School of Kalamkari was elaborate in detailing their central subject, their linework was lean, and their borders were decorative with floral prints; the colour scheme they followed was very earthy as the materials they used were natural.

Process: The Masulipatnam and the Srikalahasti schools of Kalamkari follow more or less the same painting process, as both forms are textile-based paintings.

The cotton fabric is firstly soaked in a solution of cow dung and buffalo milk for a few hours, after which it is rinsed off in running water. The fabric is then treated in the Myrobalan fruit solution to get rid of the buffalo milk smell. Interestingly, the ripened fruit is used in the Masulipatnam method, and dried fruit is used in the Srikalahasti method. Later, the iron acetate is filled in either in the negative spaces or for the borders. A kalam or pen is used in the Srikalahasti method, and wooden blocks are used for the Masulipatnam method.

All the areas meant to be red are painted or printed over with the alum solution as a mordant. After applying alum, the cloth is kept aside for about 24 hours, following which the excess mordant is washed off. For dyeing the textile red, the fabric is boiled in a mixture of water and madder root. Wax is used to cover all the parts which are not supposed to be blue. Once this step is finished, the cloth is immersed in an indigo solution; the Srikalahasti method paints the blue parts with a kalam'. The wax is finally washed off, and the yellow parts are painted using the pigment extracted from the pomegranate and mango seeds. Then the fabric is washed for the final time and dried, after which the colours in their true contrast finally emerge.

New Outlook

There have been shifts in the means of production and change in tools throughout eras. Digital printing is used to mass produce the prints, and the synthetic brush replaces the traditional 'kalam'. Although traditional methods of treating and dyeing the fabric are still in use.

In recent times, one can get the kalamkari print over just about anything, be it clothes, upholstery, home decor, or even accessories, case holders, etc. This is widely due to the technological aspect of using digital printing to mass produce these prints.

Books

Varadarajan, L. (1982) South Indian Traditions of Kalamkari. India: National Institute of Design.

Ramani, S. (2007) Kalamkari and Traditional Design Heritage of India. India: Wisdom Tree.

Dallapiccola, A. L. (2015) Kalamkari Temple Hangings. India: Mapin Publishing.