Let's learn about the miniature paintings from Kota!

Introduction

Etymology: Since these miniatures arose from the state of Kota, they are named after their place of origin.

Origin: Kota miniature or Kota Kalam, as known locally, stems from the district of Kota which is a city based along the river Chambal in the state of Rajasthan.

Location: Kota, once under the rule of Bundi's princely state, is now a province of its own. It is also one of the many regions enveloped in the state of Rajasthan.

Community: The landscape appears to have been depicted as the primary theme of compositions for the first time by Kota artists. The Chobdars claimed to be one of the few still-existing families in Kota, Rajasthan, carrying on the practice of miniature painting who worked for the Kota royal family.

Relevance: The Kota School of miniature purely celebrates the abundant greenery and fauna. The Bundi, Kota, Jhalawar, and other regional styles can be categorised as the 'Hadoti styles'. Hadavati or Haduati is a part of the western Indian state of Rajasthan and the Hada Rajput kingdom, which formerly included Bundi and Kota. It also comprised the Baran and Jhalawar districts.

History

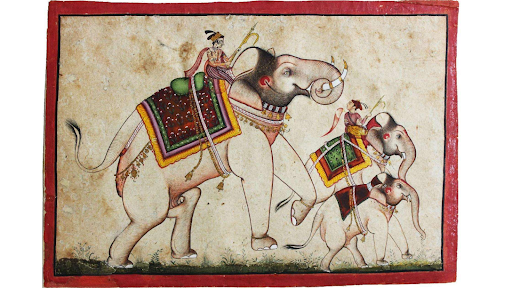

Historical Background: Since the region of Kota is based around the river Chambal, the depiction of greenery, shrubbery, and fauna is what stands out as one of the most distinctive features of Kota miniatures. Beginning in the 1660s during the reign of Jagat Singh (1658-1683), Kota had its school following its separation from Bundi. Earlier in the early period, it was challenging to distinguish apart Bundi and Kota paintings since Kota artists were taking the style of Bundi's collection of paintings. Over the following decades, their painting technique became remarkably distinctive and excelled at depicting animals and conflict

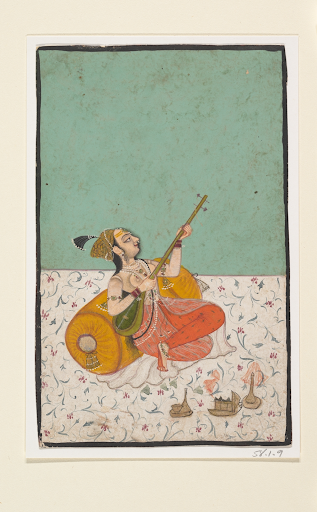

Culture and Societies: The artists of Kota extensively illustrated the Hindu epics and the Barahmasa which translates to twelve months. It talks about the pain of separation and the romanticism of seasons changing which is enjoyed by men and women. As Kota excelled in the depiction of hunting scenes, the passion for the chase, which developed into a social ritual in which even women of the court took part, is depicted in Kota paintings from this period.

Religious significance: Additionally, Kota has been a hub for the religious activities of the Pushti Margiya sect. There are countless ways that Lord Krishna has been portrayed in the Kota style. Themes, including bal leela, cow grazing, and makhan leela were mainly portrayed.

Legends or myths: The Bhils and the Hadas frequently engaged in battles. In one such conflict in 1264, Jait Singh, the younger son of Samar Singh of Bundi, killed the Bhil chieftain Kotya and took control of Akelgarh. He was so impressed by Kotya's bravery that he decided to give his newly won kingdom the name Kotah in his honour. Kotya's severed head was buried in Jait Singh's new fort's foundations. Since then, Kotya has been honoured and remembered daily at the Kotya Bhil temple.

Understanding the art

Central motifs and their significance: The delineation of verdant trees, mountain ranges, animals, and scarce architecture is of utmost importance. The themes resonating with the motifs were stories of hunting that was popular amongst other religious themes.

Mediums used: As was the case with most of the miniatures between the 16th to 18th centuries, the pigments used to paint these miniatures were obtained from natural resources such as mineral deposits from the banks of the river Chambal, various leaves, soils, and vegetation from in around the area. Natural brushes made from animal hair were most frequently used. Especially squirrel hair was utilised to make these brushes. The canvas was prepared by sticking multiple thinly aligned wasli handmade paper and fabrics to make a strong and absorbent surface to paint on.

Style: It is a contemporary style, which is almost European-inspired miniature painting. The sharpness with which the human characters are painted is in juxtaposition with the soft and lush manner of portraying their clothes. The facial features that the human characters possess are sharp and elongated noses, pointed and thin brows, oval almost round faces, and almond-shaped eyes.

Process: The process of creating these miniatures encompasses several steps. The first one is creating the canvas or base for them. Several thinly handmade wasli papers are stacked, and sometimes a layer or two of cloth is stuck to them to create a firmer base for the paintings. These papers and fabric are glued together using a naturally obtained resin-based gum. After this stage comes the phase of preparing the paints for the artwork. The colours are prepared by grinding the natural raw materials into a fine powder form. This powder is then mixed with either water or a lubricant to turn it into a liquid state to commence the first wash of this opaque pigment.

Once applying the first wash is complete, a rough sketch for the main drawing is made after which the second last stage of the process is initiated. This process entails filling in the previously prepared dyes. Once this step is completed, the second last step of painting, the linework, and detailings are done. The finishing stroke for these artworks is filling in and decorating the borders, mostly filling in the borders with a bold solid colour.

New Outlook

To contribute towards the conversation and awareness of this dying art form, INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage) organised an exhibition somewhere in 2021, in which they created a platform where Kota Kalam artists could display and market their paintings.

Books

Chaitanya, K. 1982. A History of Indian painting-Rajasthani traditions. New Delhi. Abhinav Publications.

Kathleen Kuiper, 2011. The Culture of India, Britannica Educational Pub. in association with Rosen Education Services, New York.