Let's explore the art of Indian tribes- Kurumba Art

Introduction

Etymology: Since these paintings are made by the Kurumba tribe of Nilgiri Hills, this art form is named after the tribe.

Origin: Believed to be 3000 years old, Kurumba paintings originated in the Nilgiri Hills of Tamil Nadu.

Location: This art form is practised by many districts throughout the states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.

Community: Traditionally, the male priests or temple authorities would be responsible for the execution of these paintings in the villages. The Kurumbas are occupationally honey collectors and cattle-gatherers.

Relevance: It is an expressive art form that captures the socio-religious ethos of the Kurumba tribe, and these paintings only appear on their house walls and floors during festive occasions.

History

Historical Background: Since this art is practised in a hilly region, the wildlife and greenery surrounding the Kurumbas impact their occupational activities, and their socio-cultural activities, which gets reflected in their artistic expression. The impact of their occupational activities of cattle-gathering and honey collection is depicted in their paintings, music, and dances.

Religious significance: The Kurumbas believe in worshipping their ancestors, gods and deities. They also worship Dolmens and Megaliths. They ask for protection from them whenever they harvest honey. They say a prayer as they fumigate the beehive believing that their deities would protect them from any injuries.

Culture and Societies: Apart from their paintings, the Kurumba tribe also indulge in other artistic practices such as music and dance which prove to be a very important element to their socio-cultural fabric.

Legends: As origin mythology dictates, Toda, Kurumba, and Kota tribes were three brothers created by the Almighty. These three brothers would disobey their parents or fight with one another; seeing this the almighty assigned each of them a different path in life and expected them to exchange their goods and services. Hence, the descendants of these three brothers became the three tribes Toda, Kurumba, and Kota and have been bound together ever since.

Understanding the art

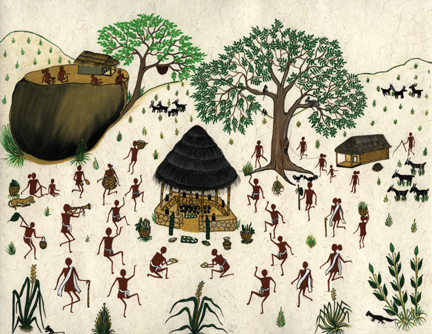

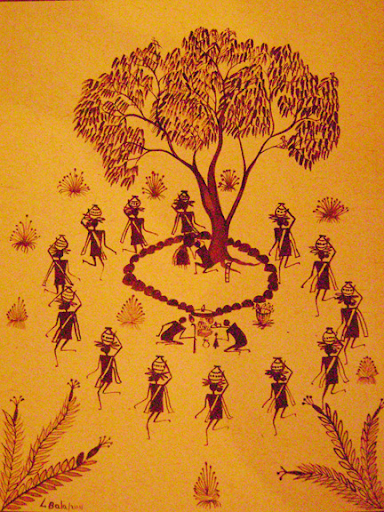

Central motifs and their significance: Daily life activities of the Kurumbas are illustrated largely, portraying themes such as women drying food grains, men collecting honey, cattle gathering, wedding, rituals, and flora and fauna with special emphasis given to wild forest animals. The documentation of collecting honey is of primary focus and is spoken of elaborately and extensively.

Mediums used: Traditionally, these paintings were created using a natural paintbrush made of burnt twigs. The pigments used to colour these paintings were obtained from different types of soils, leaves, and stones that were available around them. The resin extracted from the bark of the Kino tree would be used extensively as colour binder.

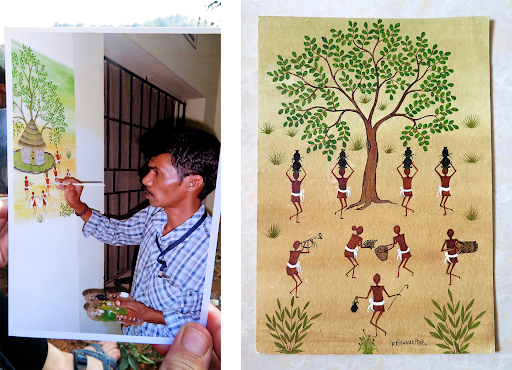

Style: These paintings are abundantly expressive in the depiction of their social, cultural, and religious practices. They also describe the various facets of their daily life, especially focusing on motifs that pertain to the wildlife around them. These paintings observe an earthy colour palette, but the colours red ochre and white especially stand out as they serve a contrasting aesthetic to their environment. Their depiction of the human form is stylistic and moderately geometrical. They appear as silhouettes because they are outlined and filled in with the same solid colour, which often is red ochre. Textured patterns of dots and stripes are drawn to add details and decoration.

Process: Since Kurumba paintings have been wall and temple paintings traditionally, these paintings were created by firstly coating their mud walls with cow dung which was left to dry for a day or two. Later on, they would paint the illustrations over the walls. Although, now instead of cow-dung they opt to overlay the walls of their homes with plaster onto which they proceed to paint.

New Outlook

This art form has seen changes in the surface it is painted on and the materials used currently. The ancestors of the Kurumba tribe used to draw on rocks, later on, the tribals shifted to temples and walls, and eventually, they shifted to painting on paper. The same goes for the traditional mediums. The raw materials that they used earlier have now been replaced by various watercolors.

Books

Rozwadowski, A. and Hampson, J. (2021). Visual Culture, Heritage and Identity. Oxford: Archaeopress.